Continuing our Black History Month series, Together trustee, Kat D’Arcy Cumber, writes about her and her family’s story. Her piece highlights the multiplicity of experiences and relationships which make up her identity in Britain today.

My sister shared a meme in our family WhatsApp group the other day – a photograph of a billboard poster with the words ‘We did not come to Britain. Britain came to us’, surrounded by flags of what these days we call the Commonwealth. My Mum’s response:

‘I love the message. We were asked to come to the UK after the war, to help rebuild. Now they want to throw us away.’

Mum arrived in ‘Mother Country’ 60 years ago from the Caribbean. From an island that, as she has told me so many times had been ‘seven times French and seven times British’. A bright child, she was educated at the Convent school, a first-class British education leading to a love of Shakespeare, which she passed on to me. But because she was too black and had the wrong name, she was unlikely to have the opportunities of her fairer skinned peers. However, Mother Country needed workers and so she took up the offer. Aged 20, she came here alone. She worked hard: waiting tables at Joe Lyons, keeping books for the GPO (where she met my dad), then as a counter clerk and, later, office manager for the Post Office. My mum is a force of nature who raised us while often working three jobs to make ends meet. She is and always has been British.

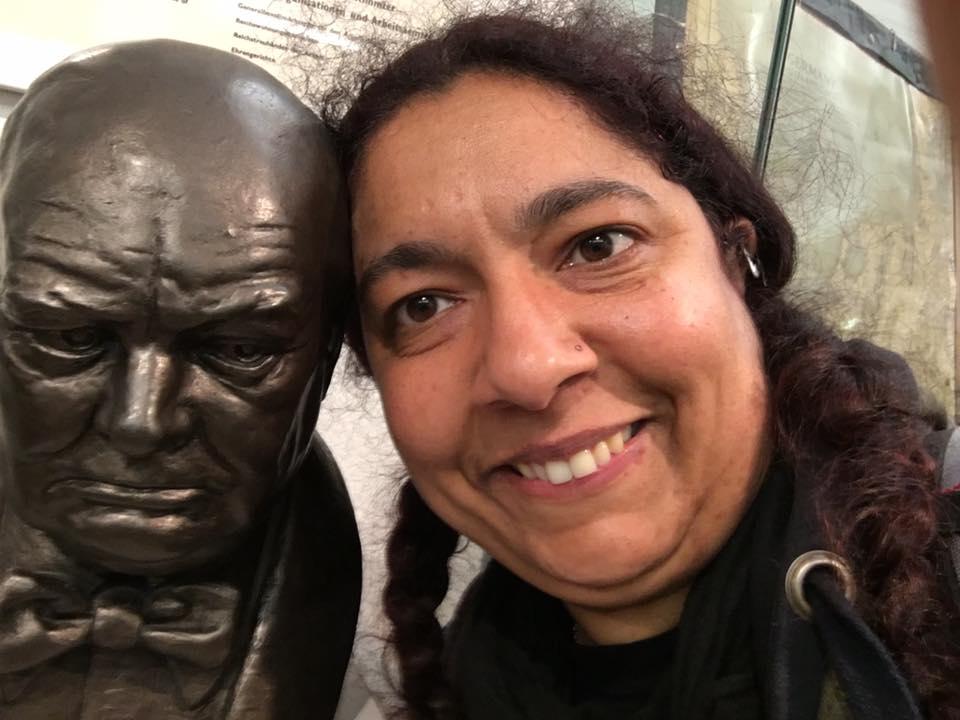

I was born in what had been the constituency of Sir Winston Churchill – even Dad, despite his Labour allegiance, proudly told of sitting in Churchill’s car during a campaign rally when he was a child, and what a great man Churchill was. I still give Winston a wave when I pass his statue near my old school.

Growing up on the edge of London in the 80s, and living in a predominantly white area, I endured the name calling, which I think I largely dismissed because what they called me had nothing to do with where I was from anyway. I’ve had the ‘where are you really from?’s and the time a lady at our church in Dorset asked if the hat I was wearing was because of my country – it came from the YHA shop in Oxford. I’ve played in a brass band, been a bellringer, love cricket, WWII planes, King Arthur, Vaughan Williams and a decent, strong cup of tea. There was a time in my life when I’d have said that I didn’t even see colour. It is only in much more recent years that I have come to appreciate the significance of being British, but not white.

On Brexit day in 2016 we flew to Rome for a conference at the Vatican. We voted, headed for the airport, and prayed. That evening outside a pavement café I sat and read of the result and what happened next. People being accosted in the street, my sister verbally abused in her local corner shop. I was frightened to come home. Suddenly, because of my skin colour I wasn’t welcome – like the rejection of the EU was an opening of the floodgates. Of course everything died down again quite quickly. I wasn’t accosted in the supermarket. Life carried on.

When George Floyd was murdered what followed became a deafening roar. Everyone had an opinion. It was overwhelming. The message seemed clear: know your place, don’t make a fuss, all will be fine. Ask to be seen, to be treated the way others are treated, and you’ve asked too much. And yet there did seem to be a change. I noticed it on the TV and at the theatre. I’d often wondered why I was usually the only brown person in the audience. Suddenly there was more diverse casting, and more diverse audiences. It felt hopeful. Like there was room for people like me after all.

I love a flag. The first time I took myself to church was as a Girl Guide at the Remembrance Sunday church parade, when I was so proud to carry the flag. I have a flag pole in my garden and a drawer full of different flags ready to fly whatever is appropriate for the season. I’ve proudly waved my union flag as I’ve sung along (albeit whilst crossing my fingers for some of the words) to the Last Night of the Proms, and bedecked my house in bunting to celebrate VE Day. And I’ve always felt proud to be British. Until now.

I know not everyone who flies a flag has bad intentions, but the current iteration has left me feeling anything but patriotic. Because it comes with a darker message. A message that starts with reducing humans to their legal status. A message that says, ‘you are not welcome here’. A message that very quickly moves towards rejecting not only those who are here legally, but also people like me who are British and always have been. And yet are told that we cannot possibly be so because of the colour of our skin. Where I live, the stream of thinly veiled racism in local press and social media goes unchecked and the flags are everywhere, a constant message that you do not belong. It is so difficult to avoid the waves of despair and fear, the wondering what happens next. You only have to look at what is happening in the US – a hijacking of church and God, driving a wave of nationalism that is anything but Christian. And it is starting to happen here. I’ve heard it in my church, in Christian groups online and from the floor of the synod chamber.

For me the questions remain: how do we ride this storm? How do we hold on to the hope that this too will pass? And when will I feel proud to fly my flag again?

Leave a Reply